Recent Google scandals have raised concerns about search result fairness, accuracy, transparency and the ethics of big brands’ dominance.

This article explores how these factors collide by examining Google’s use of search engine results page (SERP) list-based features to further their monetary gains while going against their own content guidelines and advice.

By the end, you will see how list-based SERP features directly copy programmatic SEO practices, which Google’s own spokespeople have long labeled as spam.

These features not only fail in their promise to enhance the user experience but also diminish the visibility of legitimate publishers with original ideas, worsening the search landscape.

How From sources across the web came to dominate search results

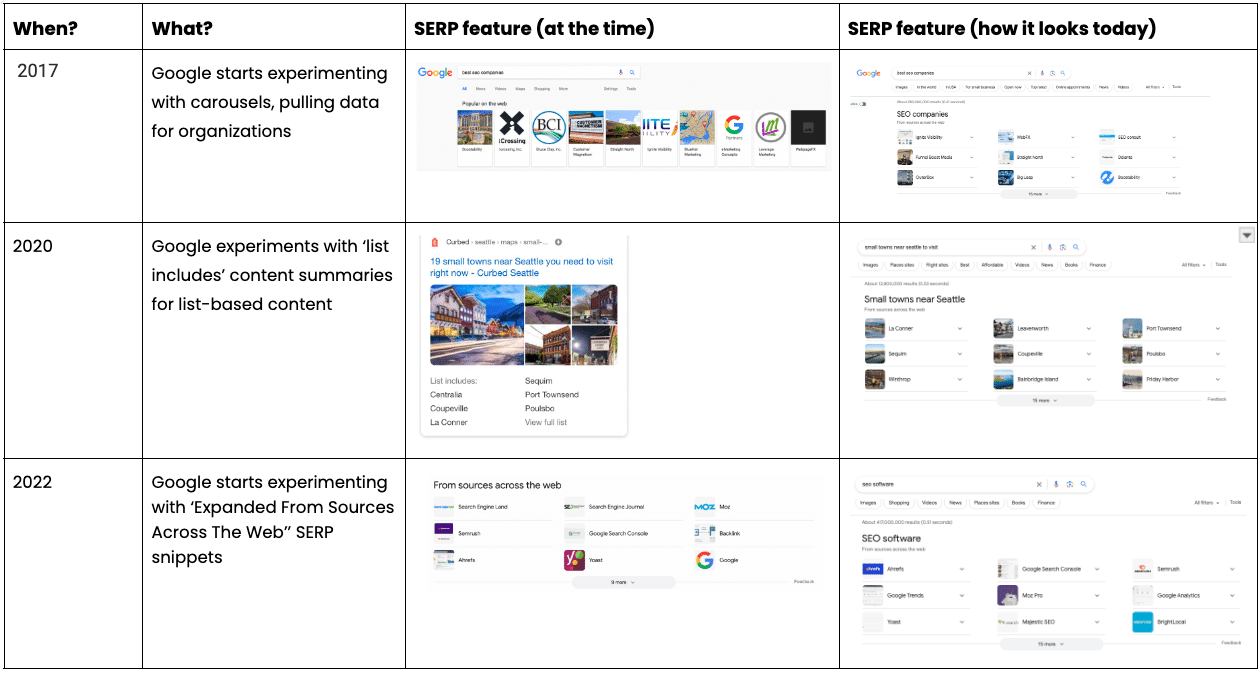

Google started experimenting with carousels to 2017 and later, around 2020, introducing content summaries for list-based content.

Around 2022, Google started introducing a SERP feature, From sources across the web, which today appears to have replaced all previous list-based content summary SERP features.

Google now uses From sources across the web for a variety of search queries, mainly with commercial intent, such as:

- Best (e.g., best date spots in {city}, best small towns near {city}, best {service provider}, best {software type}, best {software type for})

- Checklist (e.g., YouTube checklist)

- {type} software (e.g., SEO software, analytics software, ERP software)

- Date ideas in {location} (e.g., date ideas for couples in Dallas, date ideas for families in California)

- {industry} tools (e.g., SEO tools, SaaS tools, Analytics tools)

How the From sources across the web relates to programmatic SEO

When people think about programmatic content, often they think of content generated programmatically (via ChatGPT or equivalent) or spam (as Google spokespeople have referred to).

Programmatic SEO is actually database-driven. All information is organized in a database, which then populates dynamically a page template to create unique pages.

The content aspect of programmatic SEO (i.e., populating the database) can be generated programmatically (i.e., via generative AI), but that has not historically been the case.

Typically, it’s pulled from the internal databases of big enterprises. For example, think about these databases and how they are used:

- The hotel list of booking.com is used to create content in formats like {hotel type/descriptor – e.g., luxury, family} hotels in {location}

- The flights database of Expedia is used to create content in formats like cheap flights to {destination}

- The company database of G2 is used to create content in formats like best {industry} software

To populate the data in this SERP feature, Google is pulling data from the most prolific list-based content websites, which in many industries are also big enterprises and combining it with its own data on entities and brands.

This is described in some of their patent filings, specifically patent US11720920B1 from 2021, which describes a content management system or storage system (otherwise – a database) where eligible content items (entities, brands) are combined with top search results to create a combined search result item.

This practice directly aligns with the description of programmatic SEO or otherwise – database-driven content structured via a reusable template before being presented to the user.

Let’s explore the use of this in detail.

How this practice is worse for both users and publishers and why Google is doing it nonetheless (Spoiler alert: it’s money)

Now that we’ve covered the basics and how we got here, let’s explore the age-old question:

Does this actually improve search results and the user experience, or is it yet another tactic that Google uses for its gain?

Breakdown of SERPs accuracy, authoritativeness and overall quality in relation to search intent

Let’s dive into a searcher’s journey. Consider the query [best SEO consultants], where we encounter the From sources across the web SERP feature.

We want to assess the information’s validity and its relevance to the query. From the image below, we can draw the following insights.

There are 24 slots for SEO consultants to be added:

- Only 14 of those slots are filled in by actual SEO consultants and 10 of the entities mentioned are organizations or agencies.

- 7 of 14 people mentioned in the SERP feature no longer have an SEO consulting practice, meaning – they have either now moved on to other companies (including being hired by Google), founded their own companies or are no longer taking SEO clients

- Only 2 out of the 14 people mentioned in the SERP feature are women and only 3 are people of color.

- Out of the 24 slots in this SERP feature, only 7 of the slots are filled with data that directly and accurately addresses the user query.

(We now have yet another hurdle to surpass to get a leveled playing field as women or minorities.)

Let’s take it a step further and answer the question – where is Google pulling this information from? It’s Google, so they must be using some quality sources and a good variety of them, right?

Well, no.

Upon inspecting the sources further, we can note several major flaws with the selection of sources that inform this SERP feature:

- Google chooses sources that clearly do not match the search intent, e.g., SEO expert ≠ SEO consultant

- Google sources information from non-authoritative, non-factual, affiliate/sponsored link sites or spammy websites.

- For context, out of 80 links featured as part of the “best seo consultants” search results, there are:

- 30 from LinkedIn Pulse (primarily AI-generated content).

- 7 from icreativez.com.

- 4 from Medium blogs.

- There are very few links in the sample (see below) that would be considered good and definitive sources to use for such a query.

- There are only 27 unique sources that informed this SERP feature.

- For context, out of 80 links featured as part of the “best seo consultants” search results, there are:

- Google does not feature any original research to create these panels.

- Google does not fact-check the information featured.

- Google does not use all of the web sources available to it to create these summaries.

What are Google’s motivations for doing this?

I imagine what many of you are thinking, “Well, if they actually analyze all web sources to create these panels – imagine the costs involved in delivering this information at scale, with precision.”

Yes, that’s true. Aside from being costly and resource-intensive for Google to do correctly, it will also involve not relying on links or click data but actually understanding the content of webpages. But as Google has hinted in their antitrust trial, they likely don’t know how to do this yet.

Dig deeper. 7 must-see Google Search ranking documents in antitrust trial exhibits

Still, we have to understand why they are doing this in the first place. What type of websites usually invest in and benefit the most from programmatic SEO (database-driven) content?

The first thing that comes to mind is big enterprises with huge databases because that’s what you need to run a successful programmatic SEO campaign. Think:

- Expedia, TripAdvisor, Skyscanner, Booking.com in travel.

- Zapier, Canva in SaaS.

- G2 and Clutch in reviews.

Representatives from Expedia and Booking.com testified against Google in the antitrust trial. They accuse the organization of monopolizing search results by unfairly promoting their competitor micro-organizations (like Google Flights and Google Hotels) and introducing changes to search results pages while simultaneously raising advertising prices to push competition away.

Going back to the From sources across the web snippet, the only way to surpass this block of text is to pay for a sponsored placement.

List-based queries are entirely a pay-to-play game now. Pay a third party to feature you in spammy lists or pay Google to appear before the SERP feature as a sponsored post.

That’s just another way for Google to directly target companies that would otherwise dominate the search results organically for these types of queries, making sure that either the companies pay them for visibility or they lose on user clicks to their website. Yet again, that’s nothing new.

While there is no research looking at click interactions with this particular featured snippet, data from 2017 showed that featured snippets appear at the top position in about a third of results.

There is also a rise in the number of clicks they receive on average – 2017 data showed featured snippets receive around 8.6% of clicks when in Position 1 on average, while a more recent study from 2022 revealed that this number has risen to 35.1%, meaning on average featured snippets received 35.1% of the total click share.

Since these two studies were published, featured snippets appear to have become even more prevalent – in terms of screen size and how often they surfaced. I imagine a present-day study on featured snippets would be much gloomier for clicks on organic results.

This practice hurts not only users and publishers but also the search and information landscape

Beyond all of these issues, this practice enforces a very big problem – it demotes truly unique and original ideas, worsening the search and information landscape.

In many cases I looked through as part of my research, the user is worse off with the information listed in the SERP feature than if they were to visit any of the top-ranked pages.

Let me explain.

Suppose you have or work for an independent website and your niche’s search results are dominated by these snippets when you start creating your content in a listicle format.

In that case, you will need to look at the top-ranked results and the search snippet data and, to a degree, replicate the data in them as part of the list you create.

But, the key thing that any reputable consultant will say is to improve the list by adding new ideas, concepts, original data, research, new perspectives, etc.

So, you include a bunch of original, highly relevant ideas in your lists. Ideas that no other website has written about. Would they be featured in the snippet? No.

Not unless other sites mention them, too, at which point they will no longer be original. Your small website is unlikely to be featured anyway due to a lack of perceived authoritativeness. (Otherwise, links or whatever other metric Google uses to determine which websites to include in the snippet).

So, to get a placement in this feature, inherently, your list should mention things that other websites have mentioned. The presence of the SERP feature means that the user needs to click on your article specifically to see the original ideas. By default, the user sees only unoriginal ideas as part of the SERP’s top result – the snippet.

This creates a vicious loop of unoriginality, fuelling top results for queries, which are highly important for users and publishers alike. In my opinion, this is one of the reasons why people turn to TikTok, YouTube or forums to get more personal recommendations and original ideas for this type of query.

Why I care about this – and why you should, too

To recap, here are some of the key issues:

- Google’s From sources across the web is, by definition, a programmatic SEO format, but it’s not a format that uses any original content.

- The information in Google’s databases, informing the snippet, appears not to be fact-checked or frequently updated and often presents information from a limited number of low-quality sources that do not align with the user’s search intent.

- These snippets dominate commercial intent queries, often taking the first position when they appear in search results and can only be outranked by sponsored slots.

- In many ways, the entire process of how the snippet is built and how well it addresses the search intent is against Google’s own content quality guidelines. Yet, the same are applied to demote independent publishers.

- Overall, this featured snippet leads to the erasure of original ideas and, in some cases, even disadvantages entire minority groups, all done for the sake of higher ad revenue on Google’s end.

I have a sense of what many readers will say in relation to my analysis, and I want to dispel some myths:

- “You’re not a good SEO! If you’re a good SEO you wouldn’t be worried about this and you will just find a way to be featured in the snippet, one way or another.”

- So, unless we all decide to put on our black hat and ditch any integrity in how we do our work, we’re screwed?

- “Google has a duty to shareholders to keep costs down and raise profitability.”

- As a shareholder, I understand that. I also think they have a duty to people who do billions of searches on their platform daily to surface accurate information based on authoritative sources relevant to the user query and overall move toward better quality search results and improve their product, Google Search.

- “If they only change which pages they pull the information from, the problem will be solved.”

- I disagree. Fundamentally, this snippet reduces the visibility of truly original ideas. Its structure and design fail to provide the much-needed context on the included list items, their relevancy to the user’s search and the selection process behind the list items and sources added in the snippet.

I hope that collectively, as an industry, we can advocate for change and compel Google Search product managers to heed our concerns.

This analysis aims to shed light on the challenges faced by users, service providers, and publishers, illustrating why ranking organically for commercial intent queries has become increasingly challenging without resorting to sponsored placements on third-party sites or Google Ads.